Elevator pitch

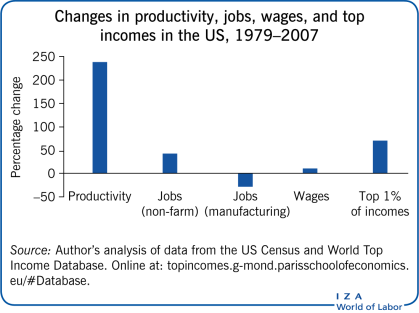

Globalization and automation have brought about a tremendous increase in productivity, with enormous benefits, but also a dramatic reallocation of jobs, skills, and incomes, which might jeopardize the full realization of those benefits. Current social policies may not be adequate to successfully redistribute the gains from automation and globalization or to advance the reallocation of jobs and skills. Under certain circumstances, an unconditional basic income might be a better alternative for achieving these goals. It is simple, transparent, and has low administrative costs, though it may require higher taxes or a cut/reallocation of other public expenditures.

Key findings

Pros

Unconditional basic income might be an efficient way to redistribute the benefits from automation and globalization.

Since it is not conditional on income, unconditional basic income does not create “welfare traps.”

Unconditional basic income is simple and transparent, with low administrative costs.

Unconditional basic income serves as an efficient buffer against shocks and systemic risks from automation and globalization.

Some evidence from experimental studies suggests that unconditional basic income might have positive effects on labor supply, responsibility, and investment in human capital.

Cons

Unconditional basic income might require higher taxes, or cuts to other public expenditures.

Microsimulation studies suggest that unconditional basic income might reduce labor supply.

Unconditional basic income might lead to a reduction in effort, motivation, and autonomy.

Unconditional basic income also benefits the “undeserving.”

Author's main message

Economic reasoning and empirical evidence suggest that, under certain conditions, unconditional basic income might be an important policy innovation for redistributing gains from automation and globalization, building a buffer against shocks and systemic risks, and generating positive labor supply incentives among the poor. While such a policy is simple and transparent, financing it might require higher taxes or cuts of other transfers, with efficiency and equality losses. Therefore, careful redesign of taxes and transfers is needed to obtain a net benefit from unconditional basic income.

Motivation

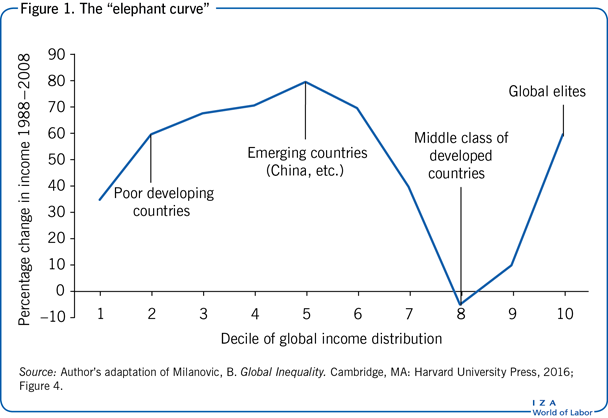

Many OECD countries have been suffering from high unemployment and job insecurity since the Great Recession in the late 2000s. More fundamentally, however, these maladies are a byproduct of automation and globalization. Along with large potential gains (brought about by more efficient production and exchange methods), these processes imply massive re-allocations, including job losses, shocks, and systemic risks. Worldwide income distribution has become less unequal, but has produced new losers, especially among the middle class in developed countries (Figure 1). At the same time, income inequality and polarization within advanced economies have increased (evident through the difference between decile 8 and decile 10 in Figure 1). There is evidence that the gains from automation and globalization might be going to the few, and may be smaller than necessary due to the lack of efficient redistribution channels. Hence, failing to design efficient means of redistributing the benefits may prevent some of the potential benefits from materializing. Designing income support policies that work well as both buffers against the volatility inherent in the global economy and as redistribution mechanisms for the gains from automation and globalization requires first considering how well current social assistance policies meet those goals.

Discussion of pros and cons

Traditional welfare under stress

There are several types of income maintenance policies, and the terminology used for them can be confusing. Guaranteed minimum income policies envisage transfers that guarantee a minimum level of income. The transfers may—or may not—be means-tested, conditional, or categorical. Means-tested transfers depend on the recipient's own income and/or wealth. Conditional transfers are subject to some conditions, such as actively looking for a job or sending children to school, or contingencies, for example, lay-offs or disability. Categorical transfers are limited to specific segments of the population, for example, age groups or occupational sectors. When defining specific policies, often the above qualifications are merged or implicit. For example, it is common to denote as unconditional a transfer that is not means-tested and does not require any conditions. Literally, a universal transfer denotes a transfer which is not categorical. However, sometimes universal is used as equivalent to unconditional.

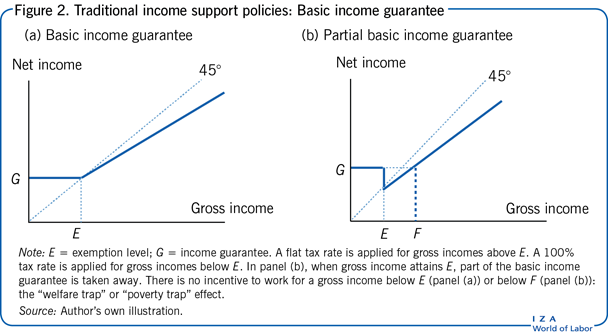

The social assistance policies of most industrialized countries are close to means-tested (and often also categorical and conditional) transfers, with a high implicit benefit reduction rate (the rate at which benefits are withdrawn as the recipient's own earnings increase). In Figure 2(a), the heavy line represents the relationship between gross income and net available income under a means-tested income guarantee. To keep things simple, the policy is illustrated under the extreme hypothesis of a 100% benefit reduction rate (a €1 reduction in benefits for each additional euro of earnings until earnings reach the exemption level, E) and a flat tax applied to incomes above the exemption level. In Figure 2(b) the income guarantee is partial since there is a drop in disposable income after E: a bad design, yet a realistic possibility. Such mechanisms are known to weaken the incentives to work [1]. In Figure 2(a), putting aside non-pecuniary motivations, there is no point in working for earnings below G, and there might be no point in working at all without the opportunity and the willingness to earn sufficiently more than G: the “welfare trap” or “poverty trap.” In Figure 2(b), the “trap” is reinforced by the drop in disposable income after E.

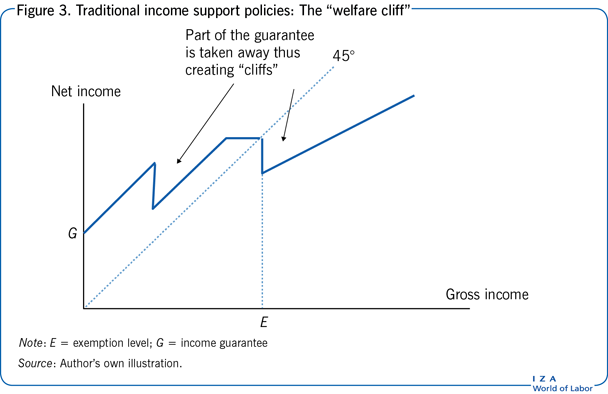

The actual policies implemented can be much more complicated than the stylized versions in Figures 2(a) and 2(b). The typical means-tested policies (and often also conditional and/or categorical) regimes tend to be a chaotic overlapping of interventions that do not favor transparency or rational decision-making by the households. These multiple measures may also increase monitoring and litigating costs and may open up opportunities for fraud and error. Figure 3 gives an example where the overlapping or combination of many mechanisms of the 2(a)−2(b) type induces an irregular profile with “cliffs”: the so-called “welfare cliffs.”

Automation, globalization, and the post-2008 recession inflated the number of people in need of assistance and, in turn, the volume and complexities of social protection. The current policies do not appear to be fully appropriate to cope with the challenges posed by the globalized and digitized economy. One line of responses to these difficulties is moving toward less protection, greater selectivity, and more sophisticated means-testing and eligibility conditions: reducing guarantees, increasing work incentives (through tax credits, wage subsidies, and behavioral requirements as a condition for receiving benefits), and narrowing the segment of the population qualifying for income support. These policies have positive effects on labor supply incentives. There are, however, also critical analyses to consider. Incentive-augmented conditional minimum income policies do not eliminate the welfare traps, nor other problems, including take-up costs, stigma, and paternalism, which lead to low take-up rates and marginalization [2], [3]. Moreover, programs focusing on wage subsidies or tax credits for low-income earners introduce additional distortions by favoring sectors that employ low-wage workers [4].

An alternative: Unconditional basic income

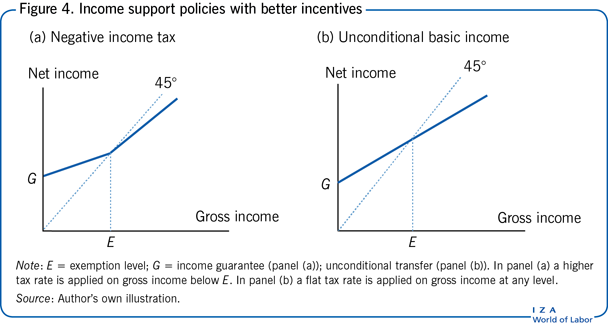

An alternative policy (as a radical replacement of, or a complement to traditional income support policies) is the unconditional basic income (UBI) [5]. It is shown in Figure 4(b), where G now represents the unconditional transfer. For the sake of simplicity, as in Figure 2, income above the exemption level E is taxed at a flat rate. UBI can be interpreted as a special case of the negative income tax (NIT) [1] illustrated in Figure 4(a). Although the means-tested income guarantee shown in Figure 2(a) might be seen as a special case of the NIT or the UBI, there is a crucial difference between the two mechanisms. In the means-tested minimum income guarantee of Figure 2(a), those below the exemption income level E receive a compensation that pushes their disposable income up to G. Their own income (below E) plays no role in determining their disposable income. By contrast, with a UBI/NIT, those below the exemption level E receive a compensation that increases their disposable income without being tied to their own income. The incentives are radically different, with NIT and UBI definitely more conducive to labor supply. In turn, there is a difference in the way proponents and supporters think about UBI versus NIT: the former as an upfront transfer that gets taxed away afterwards, the latter as a contingent transfer to people who fall below the exemption level E.

Benefits of an unconditional basic income policy

There are three main arguments advanced by supporters of UBI. First, it would update the welfare system to a new standard appropriate for the digitalized and globalized economy. It would provide an efficient mechanism for reallocating jobs and resources in the globalized economy, where employers need flexibility to compete on a global scale and employees need support to redesign their careers and occupational choices. Some experiments find that a considerable number of recipients of unconditional cash transfers use the money to cover training in new skills and related costs of changing jobs. Moreover, a UBI would represent an automatic protection against the volatility and shocks inherent in the globalized economy [4].

Second, by integrating all (or most of) the transfers into one simple and transparent mechanism, it would lead to lower administrative costs and limit the space for fraud and political manipulation. According to US estimates, the administrative cost of a non-means-tested transfer such as a UBI is around 1–2% of the total costs of the UBI. Means-testing boosts the cost to four or five times that amount. Means-testing introduces incentives for income underreporting and erroneous reporting, such as incorrect inclusions and exclusions. For example, the rate of overpayment due to fraud and error in the UK in 2010 was estimated at around 1% for non-means-tested benefits and 4% for means-tested ones. Moreover, the costs (monetary and other) to recipients of means-tested transfers are substantial, as can be inferred from take-up rates well below 100%.

Third, it would improve labor supply incentives, since the welfare-trap effects illustrated in Figure 2 would be eliminated, or at least reduced. It might also promote more efficient choices along other dimensions [5]. For example, experiments with non-means-tested transfers implemented in developing countries show positive results on labor supply and human capital investments such as education, occupation, and health.

Challenges to implementing an unconditional basic income policy

Several arguments are presented against UBI. Chief among them is the claim that such policies also benefit the “undeserving.” However, this complaint is based on a false perception. While it is true that everyone is entitled to the same basic income benefit, taxation becomes progressive (even with a flat tax rate) since the net average tax rate increases with gross income and there is a level of gross income beyond which the benefit is exhausted.

Two other critical issues when considering UBI as an alternative to current policies are the cost and the effect on effort (labor supply, motivation), including the effect of the taxes required to pay for the benefit.

The gross cost of UBI is obviously large, although the precise cost depends on the size of the benefit. The net cost depends on whether and to what extent UBI replaces other policies, as well as on the size of the replaced expenditures. Where the social protection system is large (as in the Scandinavian countries), it might be possible to finance UBI simply by replacing current social assistance policies. In Mediterranean European countries, where expenditures on income support are much smaller, replacing them would probably not be sufficient to cover the cost of a UBI transfer at a realistic level of benefits.

A related point of discussion is whether—and to what extent—UBI could replace large contingent transfers—typically based on insurance mechanisms—such as disability pensions or support for long periods of unemployment. A total or partial replacement would probably ask households to acquire a sufficiently forward-looking behavior and allocate part of the unconditional transfer to insurance and financial markets.

In general, whether a UBI could realistically replace all the contingencies and conditions on which traditional welfare policies are based is an important point of discussion [6].

Economic theory suggests that UBI might have a negative income effect on labor supply, as a higher disposable income for a given number of hours worked would induce people to supply less labor and to consume more leisure time. A UBI policy might also induce negative substitution effects—for example, if it is financed through higher marginal tax rates on income or wealth. The economic logic is that higher marginal tax rates mean lower net wage rates since the unit gain from one more hour of work declines, inducing people to work less than they otherwise would, again substituting leisure for work. However, a reduction in labor supply is a reasonable expectation from a redistribution of the gains from automation and globalization. If automation increases output with less labor and if globalization pushes mature economies toward more advanced and labor-saving processes, the redistribution of the gains might indeed imply—other things being equal—a reduction in (market-based) work.

Empirical evidence on unconditional basic income policies

Policies close to UBI and covering (nearly) the whole population are currently implemented in Alaska and Iran [7]. There is a project underway in India that resembles the Alaskan model. It is defined as a “universal basic share” ([8], [9]), a concept that can be traced back to Thomas Paine [10]. The amounts provided in each of these programs are small and complementary to other traditional income support policies. Reforms like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in the US and In-Work Benefits in the UK can be interpreted as an approximation of an NIT (complementary to other more traditional policies).

During the 1970s and 1980s, the findings of experiments on US social welfare programs are believed to have undermined the favorable attitudes toward universal social policies that characterized the political and academic debate in the 1960s and early 1970s. More recently, however, new analyses suggest that the negative conclusions originally drawn from the data are based on improper interpretation of the findings or bad experimental design.

In recent years, many experiments have been (or are being) run in places such as India, Namibia, and Uganda. Results from these reveal that universal and unconditional transfers might create positive incentives by strengthening recipients’ sense of autonomy and responsibility and by avoiding paternalism or stigma effects. Positive results include an increase in labor supply and productive activity as well as improvements in human capital (education, occupational choice, and health). Furthermore, the positive incentives created by these programs may ease the dramatic adjustments required by automation and globalization, which include a reallocation of labor and other resources. Mechanisms such as UBI can help people—financially and possibly motivationally—invest in new skills and search for jobs in new sectors. It remains to be seen whether similar results would emerge in industrial countries, but experiments are being run or planned in places such as Finland, the Netherlands, Ontario in Canada (currently suspended), and California in the US.

Another approach—so far the prevalent one in developed countries—is behavioral microsimulation. It uses data sets containing detailed information on individual choices (e.g. work choices), constraints (such as prices and income), and personal characteristics of a large sample of individuals or households. Data are used to develop a statistical model that aims to predict the choices individuals and households will make. Simulation studies have been done in many countries. Depending on the modeling approach, a feasible (fiscally neutral) policy might envisage a UBI of around 40–70% of the relative poverty line and a flat tax of around 30–45% (or a progressive tax with a top marginal rate around 50–65%). When the evaluation criterion goes beyond labor supply effects (e.g. takes into account the effects on inequality and on the values of non-market activities), NIT and UBI in most cases turn out to be superior to the current systems. Figure 5 gives an overview of studies on UBI around the world.

Limitations and gaps

Economists have given much less attention to analyzing UBI than to policies such as tax credits or conditional cash transfers. Some experiments are being done in developing countries, though not in developed countries (at least recently). Experiments are important because they permit the direct identification of causal effects. The analysis of long-term dimensions of labor supply, such as education and occupation choices, would also benefit from experiments or the use of long-term panel data.

Still missing, except for a few individual estimates, is a systematic comparison of administrative costs (monitoring, delivery, litigation) of UBI compared with conditional or means-tested policies.

There is abundant—although not univocal—evidence of the substitution effects of income-related taxes and benefits on labor supply. The evidence on income effects, however, is more controversial and less robust. Yet, such evidence is crucial for comparing UBI with alternative policies, and further studies on these topics would thus be welcomed.

Finally, relatively little is known about the labor supply effects of taxing wealth rather than income.

Summary and policy advice

The theoretical and empirical evidence is sufficient to suggest that UBI might be a viable alternative, or a complement, to selective and conditional social assistance policies. UBI appears to be an especially sound approach for redistributing the gains from automation and globalization, by building an efficient and transparent buffer against global volatility and systemic risks, generating positive incentives, and avoiding recurrent risks of falling into poverty.

Compared with means-tested and conditional policies, UBI is likely to be a winner under most criteria used for comparison. A possible exception is the cost of a UBI policy (relative to the cost of means-tested and conditional policies) and the distortions that might be introduced by raising taxes to cover the cost of the program. Alternatives to progressive income taxation should be investigated, such as a flat tax, wealth tax, consumption taxes, or environmental taxes. There may also be room to combine unconditional and conditional benefits, to some degree. Along the same lines, cash transfers conditional on recipients taking certain education or health steps might represent an interesting and less extreme version of UBI.

The UBI approach enjoys some support from many different ideological and methodological schools. As a consequence, the recipes proposed by the various sides can vary dramatically. One overarching crucial point is the relationship of UBI with existing welfare policies, and determining what eventually would be replaced by the UBI. Supporters of UBI should provide more detailed and transparent proposals on this issue.

A cautious strategy might consist of initially introducing UBI as a partial substitute for current means-tested and other conditional transfers, possibly limiting it to segments of the population identified on the basis of external characteristics, such as age and gender.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article provides a more detailed description of UBI compared to traditional income support policies and introduces UBI as a special case of NIT. It also updates the motivations, research results, empirical evidence, and references.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Ugo Colombino

Automation, globalization, and redistribution

Sources: References are listed in full in the “Additional references,” available online.